Two billion ads.

What we saw in GE2024.

Let’s start with some headline figures about the digital ads that ran during the election campaign just gone.

Overall, £11.2m was spent on them by parties, candidates and other campaigners between the election being called on 22nd May and 4th July. Of that, £8.5m was spent on Meta ads (Facebook and Instagram) and £2.7m on Google (including YouTube).

We don’t yet know how much was spent on other digital ad platforms or on services such as Spotify (where Labour bought ads on polling day), so the number will go up once the final tally is in.

All that money paid for somewhere in the region of 2 billion political ads (or around 70 ads per voter).

Polling day was the highest spending day of the campaign, with over £1.1m of ads bought (remember, there’s a media blackout that day, but it doesn’t apply to campaign ads, who can do what they want, without anyone holding them to account).

In terms of the parties, Labour spent £6.1m on digital ads (£3.9m on Meta, £2.2m on Google). Half of that was spent centrally, the other half by candidates. The Tories bought £2m of Meta ads (two-thirds bought centrally) but just £115,000 of Google/YouTube ads. The Lib Dems nearly matched the Tories on Google (£113k), but spent only £336,000 on Meta (though this was very efficient - only £6,300 in digital ads per seat won, the lowest of all parties). Reform spent £750,000, double the Lib Dems, with £625k on Meta and £125k on Google for just five seats won (£150k per seat was the highest of all the parties). 80% of their spending went through Nigel Farage’s Meta page. Lastly, the Greens spent a touch under £300k on online ads as part of their campaign to win their four seats.

Was this a lot of money?

Well, as we predicted last year when the spending limits were relaxed, it certainly was the ‘most digital campaign ever’, though it wasn’t as expensive as we might have expected (largely because the Tories were clearly financially constrained). That said, 2024 continues the unbroken streak of each election having had more digital ads than the last. (Easy prediction: 2028/9 will break the record again.)

You can view all the spending data via our Trends website.

On to the 10 things we spotted:

1/ Labour’s digital campaign was well resourced and executed. Like the overall campaign, it didn’t need to take risks

Labour’s digital ad campaign:

Had a clear message which was consistently applied. A campaign about “change” didn’t change, because nothing really came along to knock them off course. Their ads at the beginning of the campaign were basically the same as they were at the end.

Featured relatively less attack messaging than the Tories. In paid ads, there was nothing at all about Sunak, Truss or Johnson. It wasn’t exactly policy heavy, but they did fairly consistently refer to their ‘Six First Steps’ for government.

Spent a lot of time communicating that it was ok for former Tory voters to switch to Labour. Less time was spent getting their core vote out.

Clearly had a financial advantage over the Tories throughout. This likely made planning activities much easier because they had to make fewer difficult choices about resources. This was not a “Mo Money Mo Problems” election campaign for Labour.

Had space to try new things with unknown returns. They bought newspaper takeovers on the Mail, Sun, Express and Metro websites. Their Spotify ads were very prevalent on election day. Again, they had the money to do it.

Used lots of characters. Starmer fronted the campaign, but Streeting on health, Reeves on the economy, Philippson on education and Cooper on crime all showed up regularly. Lots of candidates were also well-supported by ads. By contrast, the Tories had no real people to carry their message. For example, Rishi Sunak didn’t run an ad in his name after the first week of the campaign.

More broadly, the Labour digital campaign:

Came from the position of being the ‘challenger’, allowing the party to be punchier and fun with organic content. This mostly showed up on Twitter/X and TikTok.

Was well drilled, in that things like digital community organising had been happening for a long time already, and the campaign was ready to go across all channels ‘on the B of the Bang’, when Sunak called it.

Used all means available - email, SMS, Whatsapp, web, communities, ads and more. The other campaigns were more constrained by resources.

All the above comes from experience and scale.

Labour now has a deep bench of people who have worked on digital campaigns over the past decade. This includes folks with long experience inside the party, including working on Starmer’s leadership campaign and Sadiq Khan’s mayoral elections and re-elections, the 2015 and 2017 campaign team members who returned, as well as people who have worked for the big progressive online campaign orgs. The team ended up with over 30 people on staff in HQ, plus at least the same again spread across the country helping local campaigns. Labour also pulled in agencies to add capacity where needed. This was a very well resourced campaign.

2/ The Liberal Democrats, Greens and Reform also performed well

Each of the smaller parties seemed to have sufficient resources to carry out a very functional digital campaign. All three had their targets and stuck to their list (though Reform’s was blurrier, suggesting they also wanted national vote share, even if it didn’t deliver seats). None of their target seats went short in terms of support from ads.

Reform did advertise beyond the four seats they won, into a much wider swathe of the north (in particular) in the hope of picking up more seats, or lots of second places. Ironically, the 5th seat they did win (South Basildon and East Thurrock), was one they didn’t buy any ads in, which suggests they didn’t have a totally clear picture of where exactly their support was.

Creatively, the ads were fairly predictable. Lots of “Labour can’t win here”/bar chart ads from the Lib Dems and Greens. Reform’s went with “The election is over, only Reform will stand up to Labour”. It’s interesting just how divergent this was from, for example, the Lib Dems’ media strategy. Ed Davey’s bungee jumping didn’t appear in their paid ads at all.

3/ Tory attack ads didn’t get traction

The Tory campaign was negative to start with, and got more negative over time. By the end, their “don’t give Labour a supermajority” ads, if their comments and replies were anything to go by, were prompting a “so what” or “vote Reform” response from those who saw them.

Other attempts to attack Labour, such running hundreds of localised ads claiming Keir Starmer would launch a national ULEZ immediately after being elected, or the persistent messages on tax, were also tried, chopped, changed and dropped throughout the campaign.

So did the Tory attacks fail?

If you take the lowest MRP predictions, with the Tories close to slipping into third place, then perhaps you can argue it frightened some voters back into the fold and pushed them back above a hundred seats. On the other hand, if the Tory campaign’s original ambition was to claw their way back towards a margin-of-error deficit, and start talking about a hung parliament, they never got anywhere near it.

Overall, there was no balance to the Tory campaign. They ran just seven policy ads on Meta, versus several thousand attack ads. Their digital campaign offered nothing for potential or former Tory voters to support, beyond tribal loyalty to the party (of which there turned out to be very little).

4/ The Tories didn’t have the money, and the centre didn’t work with the periphery

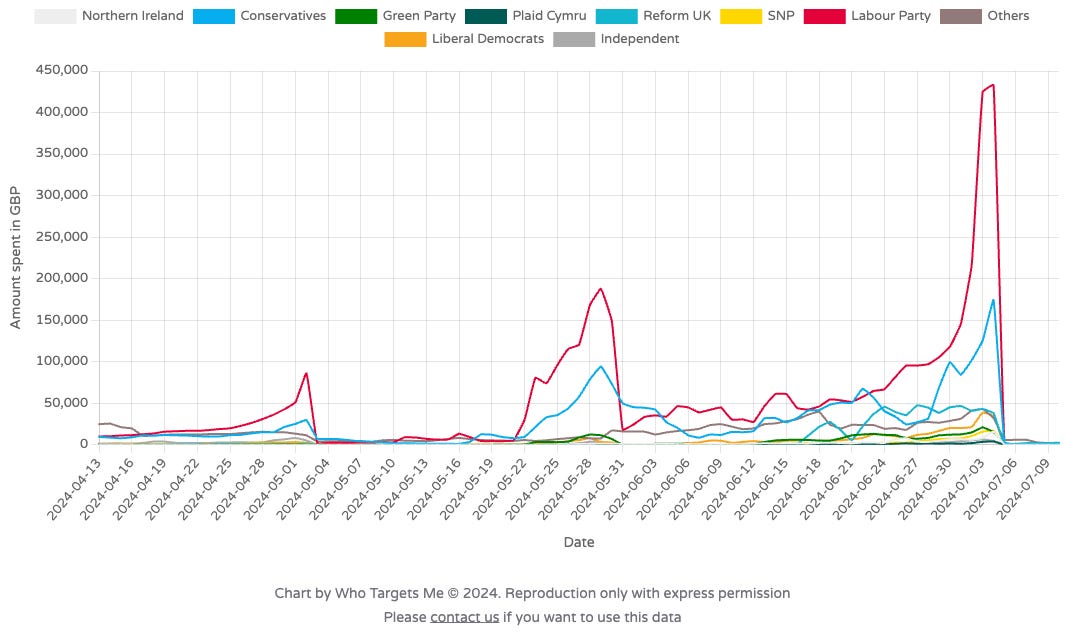

Labour outspent the Conservatives on ads in most seats they were trying to win. Election day was a case in point. On Meta, Labour and its candidates spent £433,000 on July 4th, the Tories just £174,000. On Google, Labour spent £225,000, the Tories just £1,300.

In fact, the Tories being outspent was true almost everywhere. By targeting relatively fewer seats, the Lib Dems, Reform and the Greens were all able to concentrate their efforts and pour significantly greater resources into the places they hoped to gain.

Worse, every Tory candidate appeared to stand alone. While Labour candidates were given training on how to run their digital campaigns, which images and assets to use, messages to stick to and the money they needed to pay for it all, every local Tory campaign appeared to be making it up as they went. The result was no consistency of strategy, message or brand.

Labour, the Lib Dems, the Greens and even Reform (who started two weeks late) showed more organisation and coordination, and the Tories were squeezed from every side. Their entire campaign machine will need to be rebuilt if they want to make progress in 2028/9.

5/ Despite Tory spending being lower than expected, record amounts were still spent on Meta and Google.

£11.2m of Meta and Google ads is significantly more than the £7.3m that was spent in 2019 (it was just £1.75m in the 2015 election). Tory spend increased from £1.9m across both platforms in 2019 to £2.1m this time. Labour’s digital ad spend nearly doubled, from £3.4m in 2019 to £6.1m this year.

So 2024 was the most digital election yet, though with the Tories failing to spend big, and the increased spending limits still in place, there’s still plenty of room for it to increase next time (and the time after that).

6/ Parties preferred Meta

The ratio of Meta to Google spending was around £3:£1 (the same as it was in 2019). This is most likely because Meta still offers more targeting options for political advertisers, allowing them to reach people they suspect to be supporters.

The Tories really preferred Meta, running many ads targeted at smaller and smaller audiences (sometimes as few as 100 people), as they tried to focus on those they hoped would switch back to them from planning to vote for Reform or the Lib Dems. This strategy wouldn’t have been possible with Google/YouTube ads, which really only allow age and postcode area targeting.

Earlier in the campaign, we said the Tory campaign didn’t make sense, because their ads were showing up in lots of constituencies where they had little chance of winning. We got some pushback about this from inside their campaign, arguing their ads were in fact “very targeted”.

Because Meta provides no context at all for Custom Audiences (we think they should require political advertisers to give them a descriptive name that informs people seeing the ads about what data they contain), they could have been doing all sorts of clever things with the data they’d collected in the run up to the election, and were focusing their ads more and more tightly on people they felt needed to be persuaded. Unfortunately, because of the lack of transparency, we’ll never really know.

7/ Converting Reform’s online popularity into seats will be hard

Nigel Farage has fans. Like Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn before him, and (to a much lesser extent), Ed Miliband or (to a much greater extent) Bernie Sanders or Barack Obama before that, he’s popular online. By comparison, Keir Starmer and Rishi Sunak haven’t been able to cultivate an online fandom, at least in terms of people who will spontaneously create content, like it, share it, make positive comments and so on.

An example of this is the way Reform started running ads via the party account, only to find that running them from “Nigel Farage” was more effective. Reform’s page didn’t run many ads after that. Another example is that anything anyone else posted - as a Facebook ad, a tweet, a TikTok video - got quickly swamped with “Vote Reform” comments, which in turn were liked or upvoted to the tops of the threads. Some have argued this is bot-like behaviour, but this fairly common charge is hard to prove. The same was said about Boris Johnson fans’ comments in 2019, but no evidence later emerged that showed they weren’t real people just doing things on the internet.

The future challenge for Reform will be converting online enthusiasm into seats. This year, they piled up votes where they weren’t needed, and spent money where they couldn’t win. By 2028/9, will they have a proper campaign infrastructure to turn online fandom into votes in the right places? This will be a difficult organisational challenge.

8/ Not a TikTok an election, nor an AI one, nor a particularly dodgy one

Despite the hype, TikTok just doesn’t reach enough voters to make a big difference. Turnout was just under 60%, and significantly lower among the younger voters most likely to use TikTok. Depending on who you read, Reform “won” TikTok (other readings are that Labour did), but it’s hard to make a case that it was very important to their ultimate result. Reform won seats in places with lots of older people. Labour didn’t do as well as it might have in places with lots of younger voters (losing vote share to the Greens and some independents seems evidence of that). There’s likely to have been no measurable TikTok effect at all, beyond the shift in tone that results from parties trying to create content that works there.

Similarly, AI never showed up in this election, either as a campaign tool or as an external threat. To us, this was always pretty obvious. The risks are too great for parties to use it, AI tools don’t work that well yet, the AI companies and social media platforms didn’t really want it to be a big thing (so put some guardrails in place) and the degree of personalisation feared by some is currently impossible to pull off. The US election, which is a much tighter contest, and where the political culture is so much more adversarial, seems to be a likelier victim of this, though it hasn’t happened yet. Perhaps it will in 2028.

Finally, another fear about modern elections is that they’re going to be swamped with domestic or foreign disinformation. In 2024, that didn’t show up either (and it didn’t really happen in the EU elections or French parliamentary election either).

In the past, we’ve written about the tendency to focus on ‘weird things’ in elections, like AI and disinformation, to the detriment of simply covering what parties and candidates do. The balance of this was better in 2024 (and we tried wherever possible to contribute to it), but those covering elections could still go further (more on our plans for that at the bottom) to avoid spreading unnecessary fear and distrust about the electoral system.

One example was Channel 4’s Dispatches programme which showed real voters faked AI videos and graphics to see if it could influence their hypothetical vote. It aired a week before the election, but should have been canned once it became obvious the effect in 2024 was going to be zero.

9/ The electoral system is creaky, and needs reform

We’ll set aside the FPTP vs. PR conversation, as it’s not really our issue, but plenty of other areas of the campaign showed areas where the electoral system could be improved.

First, national campaigns are ever more entwined with local ones. A candidate has a spending limit of around £17-20,000 for their own short campaign while a national campaign can spend what it wants in a constituency provided it stays somewhat generic in its messaging (and within their much larger national spending limit). This seems to help small to medium-sized political parties, particularly if they’re national, as they can run hundreds of candidates nationally while accumulating a healthy campaign budget they can target at a handful of key seats. Independents and small parties can’t do this because their budgets aren’t large enough, nor can the big ones, who are actively campaigning in hundreds of seats and whose budget is therefore spread more thinly (though obviously they get all the media attention).

Second, the spending limits themselves are too high. They’re unbalanced in favour of the two biggest parties. Smaller parties aren’t ever going to be able to raise £30m plus and compete on a level playing field. The current limits are still based on the cost of printed material, not the much lower cost of buying digital ads. The way campaigns spend money has changed, as has what they get for that money. The limits should be reformed to account for this.

Third, there’s still a lack of transparency standards for digital campaigning. We need clear rules that help the media to hold campaign activity accountable. People need to know who’s running messages in their seat, how many and which people are seeing it and what they say. Meta does this via their Ad Library, but is weak on transparency about the way campaigns use data (see our point about Custom Audiences above) and the geographical data they publish is very hard for anyone to understand (though we had a go). They’re also in the process of closing down CrowdTangle, and replacing it with something that many researchers are unhappy with. Google’s transparency is even weaker and much narrower. Other services (e.g. programmatic ads, Spotify) provide no transparency at all. We need fixed standards to improve on what the platforms provide. While they’re at it, the government can also digitise and make real-time other forms of campaign transparency (is it really that hard for a campaign to upload a receipt or a copy of a leaflet?)

10/ Digital ads are a very useful tool for real-time campaign tracking

Unlike physical, real-world campaigning, where you might be limited to mapping where the party leaders go or getting a small sample of the leaflets being delivered, when you get sufficient transparency from tech platforms, you can do interesting things with it.

We used transparency tools to build new spending trackers to follow all the money. We built a targeting dashboard to show how the parties were using different methods to reach voters. We built a map of where ads were showing up and who was running them. We started experimenting with AI summaries of ad campaigns, to see if that would give us an interesting overarching sense of the messages and themes being used in ads (we’ll be doing more on this). Our browser extension is still the only tool that sees the ads people actually see.

This allows for something of a real time view into where campaigns are putting their efforts, and helps voters see better what’s going on where they live. We think that’s going to be increasingly important as campaigns continue to invest more and more in campaigning via digital channels. And so we’ll invest more into making these tools better (if you have ideas for things we should be doing, please let us know).

11/ Bonus point - thank you!

There’s lots of people to thank:

Everyone who signed up to this newsletter, particularly those who took out a paid subscription. Thanks!

All the people who got in touch during the campaign to point us towards interesting stories.

All the journalists and researchers who took an interest in our work and used our data and insights in their coverage of the election.

The people who installed our browser extension and participated in our research with the University of Manchester.

The Who Targets Me team, particularly the folks who jumped on board at the start of the campaign to help us build new tools and analyse what was happening.

Newspeak House, an absolutely legendary institution in the world of political technology, who let us use the space in the run up to the election and who host an incredible community of political technologists.

Our funders, without whom none of this happens.

Anyone who’s fought for greater platform transparency and nudged the cause forwards over the last few years (this includes advocacy orgs, policy experts and yes, the people at platforms who built the tools we all use to try and work out what’s going on).

Lastly… what’s next?

Who Targets Me works on lots of elections. There’s a huge one coming up in the US. There may be an election in Ireland before the end of the year. Next year there’s Australia, Canada and Germany (among others).

Our goal is to continue to turn our work on political ads into ‘infrastructure’ anyone covering elections can use. This means more tools to look at spending, targeting and messaging. It means creating ‘recipes’ on how to report on the use of digital ads in politics (and digital campaigning more broadly). It means extending our browser extension to cover more platforms. It’ll mean more use of automation and translation make all this data accessible.

Alongside all that, this newsletter will continue to publish regularly, covering a mixture of campaign analysis, interviews with practitioners and policy thinking about digital ads in elections wherever they’re taking place.

If you find it useful, please share it with someone else who you think would do the same:

Thanks for reading,

Team Full Disclosure @ Who Targets Me

Fantastic work Sam and all the team

Thank you for all your hard work!