Welcome back.

For this issue, we talked with two esteemed British political scientists - Professors Kate Dommett (Sheffield) and Tim Bale (Queen Mary University of London) about digital and the forthcoming UK election campaign. We wondered what they thought had changed in the ‘digital campaign’ era, and asked them what they thought might happen next. Both conversations are below.

Alongside that, we’ve been working on some improvements to our Trends tool, which we’ll launch very soon, and doing a lot more election planning for the UK, and elsewhere. News on that soon.

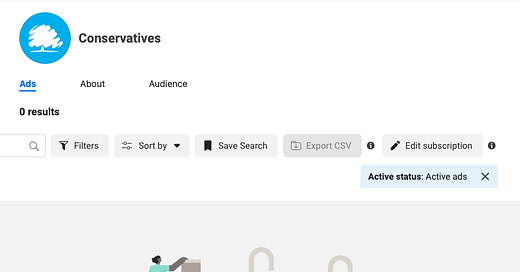

In ads this week, the Tories have switched the taps back on again, averaging around £10,000/day spent on Meta. Labour has run at about half that. The other parties… are still nowhere to be seen. Election 2024 doesn’t seem like it’s going to be a fair fight.

In the by-election campaigns, Labour’s candidates in Kingswood and Wellingborough outspent their Tory opponents 3:1 in the last week. Reform spent a bit promoting Ben Habib in Wellingborough.

If you’re interested in who’s seeing digital political ads in the UK, and the methods people are using to target voters, Fabio Votta has put together a dashboard tracking it.

Six months ago, this would have felt like a busy week in UK online ads. Since Christmas, £100,000+ spent in a week feels like par for the course. The Tories say they’re hoping to raise and spend £100m on this election (you have to assume this includes the spending of their candidates too). It’s not quite American election money, and it’ll mostly get funnelled through the two biggest parties, but they can’t splurge it on TV or radio ads, so where’s it going to go?

The next issue will be more data-heavy. Promise (threat?).

Back soon,

Team Full Disclosure

Kate Dommett is Professor in Digital Politics at the University of Sheffield. Kate has a new book out, titled “Data-driven Campaigning and Political Parties Five Advanced Democracies Compared”. She and her co-writers interviewed 328 practitioners to write it (including us). It’s a fascinating look at digital political campaigning from the inside-out.

Full Disclosure: Kate, thanks for chatting. Why did you decide to write this book?

Prof Kate Dommett: In the wake of Cambridge Analytica, we saw a lot of coverage around the use of data, that we were all being manipulated through our personal data being gathered and being used to target us with messaging that was going to affect our vote.

I had a lot of questions about that narrative. So the book is about trying to work out - what do we actually mean by data-driven campaigning? What data is being collected and how does it vary in different countries, what analysis is happening and what's the day-to-day use, as opposed to the extreme, high-profile cases such as Cambridge Analytica?

FD: You seem to start from the position that these things are a bit overhyped - that there’s more hype than reality. Is that because of the way campaigns actually function?

KD: The book is really about political parties. I think anyone who studies them knows they’re not the most sophisticated organisations. Outside the US, they’re run on a limited budget, and so they aren’t the sites of innovation we sometimes see talked about. Our hunch was that they were a lot less sophisticated than was often being said, so our interest was in understanding the party factors, regulatory factors and features of the national system in which the parties operate. How does all that affect the likelihood of them doing sophisticated things?

FD: If you’re saying the general practices may be less good than some of the hype might have you believe, it’d be interesting to know whether you think about some of the examples considered “top of the tree”. For example Dominic Cummings work on the Brexit referendum, or the aforementioned Cambridge Analytica. Were they particularly good at data driven campaigning?

KD: I think we need to be really careful about listening to people who are trying to put a particular position across and sell their success and expertise for future elections. Parties are quite risk averse organisations. They can gain from using data, but they also have a lot to lose from using it badly. We know that voters don’t really like invasive uses of data, and we also know from campaigners that they’ve experienced something of a backlash when trying something a bit too personalised or invasive.

Electoral gurus have always tried to sell you on the idea they had a huge impact on elections, but at the same time, we know having an impact on a campaign is tricky - there are so many factors outside your control.

Our work has therefore been to look at the day-to-day of campaigning and what happens routinely throughout the year. It’s that practice we should be looking at, rather than the outlier cases where the reporters might not actually be that reliable.

FD: You generally found that campaigning practices were perhaps not quite as terrifying as many people believe they are. Should we just accept this as being the way it is? What does data-driven campaigning look like when it goes too far?

KD: We’re not saying it’s entirely unproblematic, but we are saying that it shouldn’t be automatically assumed to be problematic. The problems are often culturally or systemically specific. There’s not one set of practices that are uniformly awful. Without some understanding of context, we can’t say what is and isn’t ok.

For example, in majoritarian electoral systems, like the UK, you do see specific targeting of groups while large parts of the electorate are totally ignored. That’s obviously problematic if you believe everyone should be engaged and receive information. But you don’t see the same thing in proportional systems, where parties have to reach out and talk to wider groups of people.

You need to work out what your ideals and goals are, and how the particular dynamics of your system operate and the incentives this creates, before you think about responding through privacy regulation, but could involve media or campaign regulation too. The book is about that too - the way problematic practices depend on the norms at work.

FD: What about upsides and benefits? What do you think the people you’ve talked to think they’re getting out of being more data driven?

KD: We asked all of our interviewees about what they saw as the ethical dilemmas of using data, and most of them didn’t really understand the question. Many said something along the lines of “we’re using information to contact voters to inform them about elections and how to get involved. That’s a good thing”.

It’s an interesting standpoint to flip it around. They’re people whose job it is to get the message out, and they’re trying to find people, and engage them with things they hope are interesting in a busy information environment. There’s actually a lot of potential in that, it’s just that certain tactics, such as the need to grab attention, might have negative consequences for the tone of political debate.

FD: Did you find that parties and campaigners were able to quantify the value they get from digital campaigning?

KD: They’d like to think they can, but the metrics they’re able to gather, things like engagement, clicks and so on are very hard to connect to the outcomes of elections. What people say on the doorstep, or do on the internet, can be quite different to what they’re going to do in the voting booth, so it’s a really difficult challenge.

FD: This year there are lots of elections. The UK’s will be the most expensive in history, and the US one may be too. With so many going on, you might expect to see a rapid change in the state of the art when it comes to digital campaigning. As a researcher, what would you be interested in learning about in 2024?

KD: I’m interested in the party side of things, particularly the integration of the different parts of the campaign. We've tended to see digital and the access to data that you can get through digital campaigning has often stayed quite separate to the rest of a campaign, because parties struggle to join things up. Bigger parties can do it. They can bring together in-person voter ID data, email addresses and so on and use that to serve ads. But smaller parties don’t have the capacity to link up their operations in that way. At the moment, the big parties are doing some quite extensive data collection activity online, which suggests they’re going to be pretty integrated, so it’ll be interesting to see how well the party machine can now operate as a single entity.

FD: What do you actually predict will happen in 2024? For the first time since 2015, the UK parties can actually plan for the election. They can hire, they can budget, they can sequence. From a pure campaigning technique, they should be more capable than ever?

KD: I think even with the changes to the platforms, which makes some campaigning more difficult for them, they’re going to be active across more platforms than we’ve seen in the past. Previously, they’ve only really managed presences on Google and Meta products, and even things like Instagram have been less used. This time I think they’ll invest in a larger number of platforms.

I also don’t think we’re going to see much micro-targeting, in the sense of parties trying to reach voters on the basis of multiple voter characteristics. There will be lots of geographical targeting, but overall, we’ll see them trying to reach quite broad groups.

Lastly, I think I’m expecting less innovation. US campaigns used to really expand what was possible, but everything is more set up now, and campaigns are having to work around different barriers and limitations imposed by the different platforms. They’ll try new things, but it’ll be less ground-breaking than before, and I think a lot of time will be spent optimising what works.

FD: Thanks so much Kate. Perhaps we’ll chat again after the election and get some answers to those questions!

Tim Bale is Professor of Politics at Queen Mary University of London. After every election, he’s part of the team (along with Professors Rob Ford and Will Jennings) that literally writes the book on what happened. He’s an active commentator on British politics, particularly on social media.

Full Disclosure: Tim - thanks for chatting with us. Let’s start with a small one. What do you think the impacts of the internet have been on politics generally, as well as specifically on campaigns?

Tim Bale: I think in terms of the internal politics of political parties, the internet has has accelerated the decline of deference among MPs, which has meant there are far more problems managing parties for leaders than there ever were before. Social media means people can quickly become a legend in their own lunchtimes, and they don't necessarily need to do the kind of hard yards they might have had to previously to gain some kind of profile. This has quite badly disrupted political parties.

Alongside this, if we zoom out, it's made a difference in terms of lowering the barrier to entry for new parties. For example, I find it quite hard to believe that the Brexit Party would have made such a splash in the pre-internet age.

There’s also quite a difference with regard to campaigning. It’s always said, time and time again, that the next election is going to be the “internet election” and it’s never quite been true, at least in the sense of the internet being the primary channel. But you’d be on pretty solid ground arguing that since 2015 there has been a big shift in terms of focus and spending on digital as the public's attention has moved away from broadcast and print towards social media. Overall, I don’t think it’s blown up campaigning as much as people suggested it would, though that could change.

FD: In your work you write a lot about conservative and right-wing parties. Do you think the internet favours them more than their left wing opponents?

TB: Social media is a personalising media, and a hot, rather than a cold media, so it’s bound to favour people who are charismatic, and offer sharp, simple, polarising solutions to problems. And in as much as there is often a divide between the right, (which tends to think that way) and the left (which tends to look at the world structural terms) it probably does favour the right. Having said that, there are populist left wing parties - SYRIZA in Greece or Podemos in Spain who have been successful for a time. But on average, populist right wingers have made better use of it.

FD: On the promise of whether parties have truly delivered a “digital election”, obviously the UK spending limits have just gone up massively. What do you think the dynamics of parties suddenly having many millions extra to spend will be?

TB: Election years are fundraising opportunities for parties to make the kind of money that they can then spend over the next four on the boring stuff like staffing, logistics, rent, etc. It’s worth remembering that. As for the election itself, you'll see that Labour and the Conservatives are playing in the Premier League, whereas everybody else is playing in the Championship. Just as playing in the Premier League gives you access to better players, it means they’re likely to be at a huge advantage.

The extra money will allow them more scope for experimentation. It’ll give them a chance to try things out before the autumn, which will then inform what they actually do during the campaign. They’ll be able to test their messages and ads, and ultimately to put them in front of more eyeballs. So we’ll just see more Facebook ads, more time on YouTube, more paid search terms on Google. While in the past you had to be more discerning about where you ran your ads and how much you spent, they’ll be able to saturate more this time.

FD: There are quite a few changes this election - new spending limits, voter ID, imprints on digital material. But a lot of people still complain about the way that British elections are regulated. How do you feel things are? What do you think needs to change?

TB: I think we're in a complete mess. Any incoming government, if they've got any sense of propriety or duty to democracy, will actually need to do something about the way that digital is regulated as far as campaigning goes. We’ll need to do something to make it more transparent and they should also look at reimposing slightly lower spending limits, unless we want some sort of arms race in the future.

The problem is that there’s no real incentive for the big parties to do anything about a system that favours them over their competitors. It’s the same as for proportional representation. It would probably make sense for Labour in the long term to favour PR, but in the short term, once they win, they’re not interested in it because the system worked for them.

I do worry that, in the end, nothing much will happen.

FD: As someone who works to understand and document what goes on in elections, what do you hope to learn in 2024?

TB: One thing that is difficult to get at is how parties integrate their digital campaign with their campaign on the ground. In the 1960s, people started to say that boots on the ground wouldn’t matter as much, because television was becoming so important. But that never quite turned out to be the case. There always had to be some sort of integration. We've seen people argue the same thing for digital. In the end, some people do still read leaflets, however briefly, before they shove them in the bin. People still do want to be contacted by campaigns and there is evidence to suggest that both leafleting and voter contact actually make a positive difference to people's willingness to vote and to vote in particular ways.

I’m also interested in how parties cope with the fact their digital campaigns are, to some extent, more distributed and democratised than they were before. Less centrally controlled. And that means there’s opportunities there, but also risks. How do they decide what the balance is, is going to be really interesting.

FD: Thanks again Tim. Best of luck with the big book of Election 2024 (proposed alternative title: Election 2025).

I do think Kate Dommett underestimates the change that has happened. The importance of the Conservative Brexit Referendum commitment was enormous in the 2015 election. Social media was a novel and highly effective way of communicating a simplistic solution (Brexit) to long term problems in the UK in both in that election and the subsequent referendum. Lack of effective financial regulation has also permitted a culture change in spending in UK elections. Now, spend on individualised targeting has changed UK politics to be more like the US model where large amounts of money can make a huge difference, for example, in heightening a candidate's profile very quickly.